We are locking up more and more children, but to what effect? To find out, our reporter was granted a rare three days of access to Ashfield young offenders' institution

Amelia Gentleman

http://t.co/sZRiLJWz

Inmates at Ashfield young offenders' institution. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Evening: reception

A custody van drives into Ashfield juvenile prison just outside Bristol just before 8pm and lets out the skinny, hunched figure of Ryan Lewis, who has just turned 16 and is stepping inside prison for the first time. His initiation begins in a windowless reception room, with harsh strip lighting, decorated with a small fish tank, a gloomy pot plant and posters warning new prisoners that if they bite the staff they can expect to get an extra 28 days added to their sentence. The room smells of fish and chips, which is what prisoners arriving late from court are given to eat that day while they sit in a holding cell, waiting to be searched.

Amanda Hitchens, security operations manager, in charge of reception for the night shift, asks him to give his name and date of birth, which he does with slurred words that suggest a serious speech impediment. He flicks his eyes around the room as the entry paperwork is completed, taking in the surroundings. A report from the courts says Ryan may have mental health problems and is a possible suicide risk. The form also states that he has spent much of his life in care. He is in prison for assaulting his mother.

A prison officer takes him to a side room where he removes his purple jumper for a search of his upper body, then his black jeans for a lower body search. He is asked to sit on a big grey plastic Boss (Body Orifice Security Scanner) chair to do a body scan for concealed metal objects. Occasionally staff find mobile phones hidden inside a prisoner's bottom, or drugs tied with cotton thread to their testicles, but Ryan is new to the prison system and doesn't know any of these tricks. Nothing is found, so he is given a green tracksuit and offered a hot drink from the machine, while his old clothes are packed away into a black plastic storage box, labelled with a sticker showing a photograph of his face and his prison number.

The driver of the prison van, employed by the private company GeoAmey, comments on how quiet Ryan was during the 104-mile journey from the court in Southhampton. Usually juveniles are a nuisance to drive because they are so rowdy, shouting to each other and banging on the windows at girls, he says. Adults tend to be better behaved. "The novelty has worn off," he says. Ryan has travelled sitting on a moulded plastic seat in one of the van's six cubicles. There are no seat pads because they always get torn off, the driver says, and no safety belts in case prisoners try to hang themselves.

Ryan sees a nurse and is handed back the ADHD medication, Equasym, he has brought with him, and taken across the prison to see his cell by Frances Crawley, the duty manager who has worked here for eight years.

She leads him to a cell on the second floor of the wing for remand prisoners; he follows, a short, hunched figure, holding a prison towel and new prison-issue Y-fronts in a transparent plastic bag, snatching glances with frightened eyes at the crowds of noisy prisoners who are out of their cells for evening association. Everyone is in a green uniform, but prisoners are allowed to wear their own trainers; only inmates from the most deprived backgrounds, or who have yet to receive their shoes from home, wear the white sneakers issued at reception. Prisoners tend to wear their tracksuit bottoms low, and are allowed a range of hairstyles, plaits and braids; many wear colourful chains of plastic rosary beads around their necks.

Two tiny bars of soap have been laid out on the desk of his cell, there's a television, a white plastic comb, two packets of Colgate and a pink toothbrush. In the future he will have to buy his own toothpaste and shampoo, but this is the welcome pack everyone receives. On the bed there is also a pile of sweets – a pack of Polos, fun gums, Refreshers, a Fudge bar – and some orange squash. Despite the sweets, the cell is profoundly depressing. It is narrow and (obviously) confined, the pillows and duvet on the unmade bed are yellowing and stained, and there is no seat on the toilet.

He is then taken to a windowless room on the wing to meet Cathy for the first-night interview, from which prison staff gather information they need to make sure the inmate is properly handled.

"These questions may seem a little bit personal, but try to relax; it's just so we can help you out," Cathy tells him. "Have you ever had any feelings of self-harm or suicide?"

He holds on to the arms of his chair as he listens, occasionally transferring them to his pockets and then back again to grip the armrests on his chair. His brow is lined and he looks petrified.

"No."

"Who do you live with?"

"I live with my mum. Which is the reason that I am in here, because I assaulted her."

"How are things with your mum? Have you spoken to her?"

"Not going to. Not yet."

Cathy keeps in her ear-piece throughout the conversation, so she is linked to all other staff and can be redeployed if there is trouble elsewhere.

"Have you any mental or physical health problems?"

"Yes, I've got asthma and ADHD. What time is bang-up?"

She asks him about his drug, tobacco and alcohol consumption; his attention jumps around. Later staff wonder whether perhaps he hasn't taken his drugs today, which might explain his slurred voice. He has fluff on his upper lip, too insignificant to shave off; he sounds very young.

"How do you feel about the first night in Ashfield?"

"Fine," he says, but he flits his eyes anxiously towards the piece of glass in the door behind her as she talks, through which he can see the other prisoners clustered together in intimidating huddles.

"You're not worried?"

"No. Do you know when lights go off? When do the lights go off?

"In your cell you can turn them off yourself ... You can let us know if you are being bullied."

"I can't change my bedding. I don't know how to."

"That's all right. I'll come and sort it out for you."

"Is it all right to watch TV?" he asks. "Will I be in my cell tomorrow?"

"Yes."

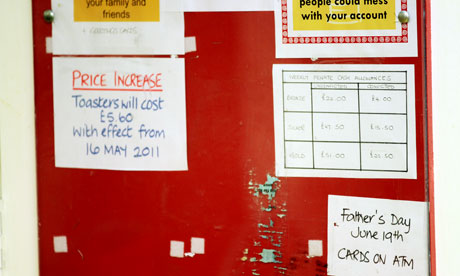

"I want to get some rosary beads." She tells him that there will be a session during the week-long induction programme during which he will be taught how to use the ATMs that are on each wing, through which prisoners can order snacks and personal items such as rosary beads. The chaplain is booked to talk to him tomorrow. "He'll give you some support."

7am. Breakfast

The youngest prisoners are housed in the USLA wing (under school leaving age). The 30 boys, aged 15 and 16 sit at rows of tables and chairs, screwed to the floor. The plastic covering and spongy filling has been pulled off many of the chairs. "Kids are kids; they pick at stuff," an officer says.

The prison is privately run by Serco, and was the first private prison in the UK to house young offenders; the company charges the state around £55,000 a year per inmate, which is comparable to state-run units. Prison reform campaigners remain very hostile towards the spread of privately owned prisons, arguing that the the existence of a profit-based model is not compatible with the goal of having fewer people in prisons.

The debate is not at the forefront of prisoners' minds, but numerous inmates who have been transferred from Feltham, which is state-run, prefer being here, mainly because they are out of their cells for much longer, an average of 9.8 hours a day.

The prisoner cleaning up after breakfast sprays Serco-brand disinfectant on the tables, and then sprays some on a fellow teenager.

Staff are expecting a fight. Since early morning, two boys have been shouting through their cell doors that they are going to smack each other. One has been locked back in his cell. But the desire to fight is contagious and as the boys mill around after breakfast, there is a sudden commotion as one prisoner punches another on the side of his face.

"We fight because they don't keep you occupied. Or because we are sexually frustrated," a prisoner says.

Both boys are put back in their cells, one with a bleeding lip; the rest are ushered back to their cells or into the yard for exercise, where it is still pitch black and drizzling. No one goes near the exercise devices in the corner of the fenced yard; instead they stand in cold huddles, complaining that the staff won't give them a football to play with. Staff say they won't let them play football now because otherwise they will be too exhausted for school.

8.30am. Mass move

Lessons are obligatory for all of the 360 inmates, who are aged between 15 and 18, and prisoners earn 40p for every class they attend, which they can spend on chocolate or credits for phone calls. Classes begin at 8.30am, but staff begin searching boys earlier, so they can be moved in small groups towards the education wing. The mass moves of the prison population between meals and classes are some of the most high-risk moments of the day, and at least 20 members of staff are positioned around the football pitch that stands between the two house blocks (each with four residential wings) and the education centre.

Because of recent changes to sentencing guidelines, the prison houses many more dangerous prisoners than it did four years ago, when around 46% of inmates were in for minor offences, such as car crime. Now, because of concerns about overcrowding, and a desire to incarcerate only the more serious offenders, only 2% of inmates are in for car crime, and the rest have been sentenced for everything from murder, drug-dealing, aggravated burglary and gang-related assaults to rape. The majority of boys come from London, and the black and minority ethnic population now stands at over 50%. There has been a surge of gang-related violence inside, linked to conflicts outside the prison walls.

The inmates at Ashfield young offender's institution can buy personal items from ATMs Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

The inmates at Ashfield young offender's institution can buy personal items from ATMs Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the GuardianA few years after Ashfield opened in 1999, there was so much fighting and rioting here that the director general of prison services described it as the worst prison in the country, and a state prison governor was brought in for a while to replace the prison's privately employed director. Things have improved since then, and Ashfield's last inspection was very positive, but fights still frequently break out. A team of officers is also monitoring the mass move on a bank of screens in a control room; at the first sign of trouble, staff are ordered to lock down the wings.

This morning the move is quiet, although officers complain about the number of prisoners walking to class with their hands tucked into their underwear. "We have this thing at the moment where everyone is walking around with their hands down their pants," one officer says. "It's really unhygienic for a start. We are constantly telling them to wash their hands."

"Ashfield is a shithole," someone shouts through a ground floor cell window.

9am. Staff morning meeting

About 13 senior staff members arrive at the administration block to discuss issues that have arisen the day before. As they wait for the meeting, they study a noticeboard with posters identifying the prison's most dangerous inmates. A summary of the week's security incidents has also been pinned up: "Threats on staff, 12; assaults on staff one; drugs three; tobacco six; weapons four; bullying 10."

There are information notices everywhere: reminding staff about the prison's values, and listing items that must not be brought inside. Prohibited items include wax, chewing gum, magnets, plasticine, toy guns, mobile phones, Blu-Tack, metal cutlery, explosives, wire, newspapers, magazines, computer memory sticks, excessive personal medication, umbrellas. Things that will be carefully monitored include tools, yeast, cling film, rope, vinegar, glue and tin foil.

Even when they shut themselves in the loo, there is no escape from the staff information bulletins. Signs stuck to the back of the toilet doors warn: "Wrongdoing! Are you worried about staff members partaking in corrupt/unethical practices? Are you aware of young people offering gratuities or gifts to staff members?"

Officers run through a handful of incidents: fights, assaults on staff, blows exchanged in the gym, a stabbing of an inmate with a home-made weapon, a screw melted into the end of a toothbrush handle. One inmate threatened to punch a female teacher in the face, and there was a sexual assault on another female teacher by a prisoner who rubbed his hands between the top of her legs. "The teacher is quite shaken and still a bit teary when she talks about it," a colleague says. The list of problems is not unusual and the meeting is quickly wound up.

9.30am. Discharge

Mohammed, newly 16, is being released after four months here for an aggravated assault. As he prepares to leave the building he is adamant that his first exposure to prison has put him off committing any further crimes.

"I felt very scared when I came in. I couldn't cope with prison. I was in healthcare for trying to harm myself, banging my head against the walls, trying to hurt myself with the curtains. I was just feeling it really hard. I thought, you might as well die."

Does he think prison has worked? "It has worked. It has. If I am going to do something bad, I will think about prison and I won't do it.

"It's a boring life in here. Some people are here for two years. I don't know how they do it. I'd harm myself."

He isn't sure what he will do now. "I don't really know. Try looking for college."

A lot of the prisoners are less certain that prison is a deterrent. Jason, 17, who has stayed in seven different prisons since his first visit at 14, says prison no longer has much of a negative effect on him.

"At first it was a bit of a shock to the system not having your family around, and then I got used to it," he says. During his time inside he has learned a number of useful things from other prisoners. "How to weigh up drugs and sell them, how to make a profit on them, car theft. I've learned how to fight in jail. You've got to fight quick; it can only last a couple of seconds before you get stopped, so you've got to fight better. You go for hurting as soon as possible – fighting, kicking, biting, together."

The numerous anger management courses he has taken do not help. "They suggest the seven-11 technique – you breathe in for seven seconds and out for 11, it's a chance to calm you down. It doesn't work. If you're in that situation you don't have time to say: stop – let me breathe for a few seconds," he says. "I don't think the prison system works. It just puts a hole in people's lives."

Senior prison staff don't want to be seen to be criticising government policy, but privately acknowledge that short-term sentences do not work for young people. "Generally there is an acceptance that custody doesn't really work in the round for juveniles," an assistant director says. "We don't have the choice. The law says they are coming so we have to work out what to do with them."

The frequency with which young prisoners return to prison illustrates the futility of the system. Around three in four children sentenced to custody will reoffend within a year of release. Director of campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform, Andrew Neilson says: "We know that short prison sentences don't work. We also know that prison fails children. Yet rather than take a welfare approach that tackles the causes of their offending, we lump young people in trouble with the law together under one roof, exposing them to violence, substandard education provision and long periods of boredom." A decision to automatically jail 16 and 17-year-olds who are found guilty of "aggravated" knife offences, announced last month, suggests the coalition government will soon be locking up more teenagers.

12pm. Internal adjudication

Earlier this week a prisoner, Martin, set fire to his cell at 2am. He has been transferred to the prison's Brunel wing, the 17-bed segregation unit, a prison within a prison. William Barnes, the prison's catering manager, is chairing an adjudication, rather like an internal court hearing, to decide how the prisoner should be punished.

"I didn't want to be in my room any more ... I fucked up." Martin tells the panel of officials gathered to hear his explanation. He is startlingly pale with uncared-for teeth and slouching shoulders.

The burnt-out cell has been locked pending police arrival, but the acrid smell of burned plastic and carpet hangs around the top floor of the prison wing. Fires like this happen once or twice a month, less frequently now that prisoners are no longer allowed to have toasters in their cells. Lighters are banned, but some inmates are good at building up a flame from bits of fluff and the current from a kettle wire. Often they dampen their beds to create the maximum amount of smoke. Generally they don't do it to cause harm, staff say; it's a cry for attention, or because they want to be moved to a new cell.

"You almost died," Barnes tells him. "We had to send people in to get you out and there was a real risk to them. They couldn't see you when they went in, there was so much smoke. Have you learned your lesson now?"

"Will they hold me back?" Martin asks; he is due to be set free in eight days. Barnes tells him it won't be clear whether extra time will be added to the sentence until the police have done an investigation. It isn't clear whether Martin, who comes from a troubled family, was actually hoping for an extension to his stay.

Prisoners often start misbehaving in the days leading up to their release, staff say. "When they are in here they get food and clean clothes and a warm cell. They worry about losing that," Barnes says later.

The prison's deputy director, Brian Stewart, recalls at least three prisoners who simply refused to leave. "One was released, walked to the car park and smashed the windows of five staff members' cars; he was back here within a few days. He was homeless, living in a wheelie-bin before he came to us," he says.

"Young people often get a much better quality of care here. Some of them like the security of being here. It's often the first time really clear boundaries about where they should be and what they should be doing are set out," he says. "Sometimes people come back saying they want to finish their plumbing course, or they just say, 'You know me here.'"

It's not surprising that some prisoners aren't in a desperate hurry to go home when you look at where they've come from. A third of the prisoners are looked-after children – previously in foster care or children's homes. "Another 30% are known to social services – which means 63% are known to social services overall," Stewart adds. "It's a sad reflection of society."

2pm. Education

The attorney general, Dominic Grieve, described Ashfield last year as an "educational establishment with fences", highlighting it as a potential model for other youth prisons. Some staff members mutter darkly about the wide range of courses on offer here – with 56 teachers employed to teach everything from Islamic studies and music production, to horticulture and cooking. "They get all the education they need. They get a gym. The lads think it is like a holiday camp," one officer says, bitterly.

But the more senior officers support the principle of trying to use the time that prisoners are here as constructively as possible. "You can't shut them in a cupboard for two years and expect them to come out different. Morally we should do as much as we possibly can for these children, so they don't turn around and say society hasn't helped them," Barnes says.

Six boys are locked inside a maths class by their teacher. Most of them are barely listening as he asks them to work out how much a bar owner needs to pay his staff. The only diligent student is a 16-year-old who is two years into a 20-year sentence for double murder.

"Maths isn't my strong point," he says, apologetically, but he focuses on the lesson and is congratulated by the teacher at the end for his efforts. Young offenders are not segregated according to the severity of their crimes, so a young person on remand for shop-lifting may be housed and educated alongside rapists and murderers.

Most of the pupils are less attentive. "No I'm not fucking doing it. I told you, I'm not good at maths, man," a boy at the back says.

"What's five times one?" the teacher asks him, with impressive patience.

"Am I a four-year-old?"

"What's 480 pence in pounds?"

"Is it £480? No, it's £48, isn't it? I've never been in school. I can't do maths. I'm not following. I'm a spastic."

The prisoner looks out of the window. "Jail and school. Oh my god."

There is a one-way mirror across one side of the classroom, allowing security staff who pace the corridors to monitor what's happening inside. Two of the boys are talking to each other in loud whispers about who they want to beat up. "I reckon I'd smack him."

"Let's not talk about violence, boys. It's not a nice conversation," the teacher says.

Pens are removed from them at the end of the lesson (there have been a few incidents with inmates stabbing each other with pens) and they are searched before they can leave.

"The most frustrating thing about working here is the transient population," the teacher says. The lessons are structured on 12-week cycles to accommodate new arrivals and departures, but this short cycle limits how much he can do with prisoners. He often finds it hard to teach because the pupils have little desire to learn, or have such poor abilities that they "hide behind their behaviour so they won't look silly in class".

Over 40% of the boys have some form of learning difficulty, dyslexia or ADHD or conduct disorder, according to Emma Wilde, the prison's assistant director in charge of education. About a third of the inmates have the literacy level of seven-11-year-olds; there are six who can't read at all. The prison doesn't offer GCSEs.

"The lads would like to have them because they understand that they are valuable, but if you were going to offer GCSEs, you would have to do maths and English and most of them are not capable of getting a good GCSE in those subjects. We don't have them long enough, they've missed too much school and they aren't capable of it," she says. About seven prisoners who have done very serious crimes are studying A-level modules, in the expectation that they will be inside long enough to finish the course.

There are occasional awards ceremonies for good progress and parents are invited. "Most of them have never formally achieved anything. It's nice for their parents," Wilde says.

Afternoon. Healthcare wing

Dan Leary, an officer in the substance-abuse wing, has just found a ligature made from torn up bedsheets hidden in a boy's cell. Although there has never been a suicide in the prison, there has been a recent rise in attempts.

The boy, who is in jail for the first time, was very worried about a looming court appearance for sentencing. Outside prison, he was a heavy drinker and a regular user of benzodiazepines. Inside he will have had very little access to drugs. Relatively few drugs get smuggled into the prison; staff believe this is because it's a no-smoking environment, so prisoners focus their efforts on smuggling in cigarettes. Relatives occasionally manage to hide enough tobacco for a very thin roll-up under stamps.

This morning the boy has been transferred to the healthcare wing for closer supervision. The bars on the entrance door to the ward are painted in cheerful primary colours in an attempt to make it feel child-friendly and welcoming. Television monitors in the nurses' station show boys huddled under duvets, occasionally stirring.

Since the prison was opened, far more attention has been paid to mental health problems, as staff realised how many inmates were arriving with serious issues. A third of the prison population are on the mental health team's books, a large number are taking drugs for ADHD and depression, a significant number have low IQ, and very high levels of anxiety.

Brunel segregation wing

Ron Jones's name badge was recently reissued so that instead of describing him as a "Senior Custody Officer", it now reads "Senior Care Manager" to make his title sound more appropriate for children. In theory, all prisoners here are meant to be treated as children but this guiding principle often sits uncomfortably with the reality of life inside, particularly in the segregation wing, where prisoners are subjected to a much harsher punishment regime. Here they have no televisions or telephones in their cell, are not allowed to spend time with other prisoners, and are usually educated in isolation.

Jones is uncertain about whether he would describe the prisoners as children. "Some of the mature 17-year-olds behave in a very adult fashion. But some are very needy, and their reasoning capacity is very similar to a child's. I acknowledge that they are all children, but the size of some of them is quite impressive and they are able to do harm," he says. He has been assaulted by prisoners six times in the past 18 months.

This uncertainty is shared by colleagues in other wings. "They might be 6ft-tall, but still they'll be asking, 'When's my mum coming? Why hasn't she visited?', just like a child asking why their mum hasn't turned up for sports' day," Frances Crawley says.

Darren has been sent here because of the weapon made from a toothbrush and a screw, which he hoped to use "to inflict pain on someone I don't like". He appears profoundly depressed, but tries to shrug off his troubles. "It's easy in here. When you go to prison, you think it is going to be a bad place. When you get to know people it turns out to be fun; you have laughs. It isn't fun being here but you have fun in here."

And yet he struggles to make light of the experience of being in segregation. "When you think about it, being in your cell ... you lose your sanity," he says, smiling at his hands.

Yoga class on the lifers' wing

Ashfield is the first privately run young offenders' unit. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Ashfield is the first privately run young offenders' unit. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the GuardianSome effort has been put into making the lifers' wing a more friendly environment, and staff have fitted carpets, painted the walls light blue and installed black sofas and pinball machines. Most of the inmates sleep in larger, double cells, with their own sofa. These attempts to soften the experience for those who are here longest are controversial among staff, not least because when the boys turn 18 they will be sent to ordinary adult jails.

There are 22 people in for stabbings, murders, rape, arson. This afternoon, some are taking a yoga class, lying on mats in the centre of the wing. "Legs together. Stretch your backs," a female instructor requests. The boys begin howling with laughter because someone has broken wind.

Recently there has been some rivalry between the inmates on this wing over who has the longest sentence. Until last month, this was a 17-year-old with a couple of gold teeth who is serving two concurrent 18-year sentences for a double murder; he was disgusted at the recent transfer of a 16-year-old with a 23-year sentence. "He liked being the person with the longest sentence. We tell them it's not about who has the longest," Ian Wesley, the senior officer here, says.

Only the most experienced staff work in this wing. On the whole the boys here are calmer, but precautions are taken. A sign by the exit reads: "No young people are allowed to take socks to the gym." Socks can be transformed into a powerful weapon if prisoners put bars of soap inside them.

The inmate with the longest sentence is Ahmed, who killed two people when he was 14. "It was a shock to come to prison at that age. I was quite a child then. I knew nothing about prison. I'm the only one in my family ever to have been in prison. It was a shock for them all," he says. Outside his window, there are flowers in wooden tubs – the only flowers in an otherwise bleak, barbed wire and concrete environment.

Articulate and thoughtful, he has a better school record than most of his companions and has had longer than most to consider whether prison works.

"It does for some people, but for people who just come for a few months, they just see prison as a joke. It's fun for them, they're getting gym and everything they want. Some people prefer it in here," he says.

He is less willing to focus on his own experiences. "The past two and a half years ... I got arrested, I was in court, in prison. Everything is a blur. Honestly, I do think that I won't be able to cope if I dwell on my future. It drains you. It stresses you. I don't like to talk about it."

Evening handover

The night staff arrive and study the log-book that contains all the days' incidents. "Notice of minor report: Ignored staff request to take hand out of trousers," one report reads. "At approximately 14.50 hours, Brian was deemed to be disrespectful to a member of staff by saying he had an erection, and pulled his trousers tight so he could see. He also said he would take it out to show it."

Boys are locked up at8.15pm. Well-behaved prisoners can watch television until 2am in their cells; around 15% of inmates have had their TVs removed because of bad behaviour.

There's a lot of banging from inside the prisoners' cells as they are locked away from the night.

"That's just what they do. Bash their doors to get attention," an officer says. He is so used to the noise that he barely registers it. "If an officer responds to every bang on the door we would never get anything done."

But Louis, 17, a notorious London gang-leader, currently ranked by staff as one of the most dangerous inmate, is fed up with all the noise.

"You get the ones who bang on the doors. They can't hack it ... they self-harm, screaming, setting their jail on fire. I used to feel sorry for them. Not any more," he says.

"Jail is just shit, isn't it? How can they make you better if you're locked up with all your enemies?"

All names of prisoners and staff have been changed at the request of the prison. This is a condensed account from three days spent at the prison.

No comments:

Post a Comment