http://jjie.org/how-safe-georgias-youth-detention-facilities/55466 via @jjiega

The beating death this week of 19-year-old inmate Jade Holder at an Augusta, Ga., Youth Development Campus (YDC) is the latest in a series of incidents that have renewed focus on safety levels within Georgia youth detention facilities. Last week, for the second time in six months, county police were called on to quell a riot at the DeKalb County Regional Youth Detention Center (RYDC). In May, a murder suspect escaped from the DeKalb RYDC, only to be found and returned a few days later. And in July, the Eastman YDC was the scene of a fight that led to an investigation by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI).

These incidents have all come after an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice over implementing changes at the facilities, something that was supposed to improve and stabilize the system. That agreement came after a DOJ investigation in 1997 found serious abuses, including overcrowding and abusive behavior by staff. Georgia agreed to improve conditions and signed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the Department.

While the MOA, which ended in 2009, led to improvements in education and medical care at the YDCs and put the focus on rehabilitation, it has failed to totally safeguard inmates and those officials working in them.

It may be uncertain how deep the problems run within Georgia’s YDCs, but there are some clear issues within at least a few.

In the Eastman facility, for example, a number of people who have worked there say both inmates and staff are at risk. Dormitories are often under-staffed, they say, and attacks against guards and between inmates are a regular occurrence.

Victoria Floyd was a juvenile corrections officer inside Eastman for four years from 2007 until 2011. She says she was assaulted multiple times by inmates who threw urine and feces on her and in one instance an inmate groped her buttocks.

“Those things happened because of poor staffing,” Floyd said. “Those times I was assaulted, I was the only officer in the unit or the only officer escorting residents.”

According to Floyd, she was routinely assigned by herself to guard dormitories housing 32 male inmates. In a perfect world, Floyd said, a unit would be staffed with three guards who would divide the inmates between them. In reality, Floyd felt fortunate if she was assigned a unit with one other guard, taking 16 inmates each. At times, she said, she didn’t feel safe.

Another former Eastman guard, who wished to remain anonymous, said the 32-to-1 ratios were not unusual at the YDC because the staff was too small, leading to high levels of violence. According to theDJJ policies manual, each facility sets it’s own standard ratio.

A DJJ official, however, said the ratio at Eastman, a facility that can hold 330 inmates, had been set at 16-1.

The environment inside Eastman, the former guard said, which houses older inmates aged 17 to 20 committed for violent crimes, is anything but positive. He added he was assaulted twice while he working as a correctional officer.

Department of Juvenile Justice Commissioner-designee Gale Buckner declined to comment when asked what her assessment of Georgia’s YDCs are because she has not yet had a chance to assess the situation for herself.

Buckner was appointed Commissioner after Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal assigned former Commissioner Amy Howell to a new role in another state agency. Buckner joins the DJJ at a difficult moment for the agency following the beating death of Jade Holder at the Augusta facility.

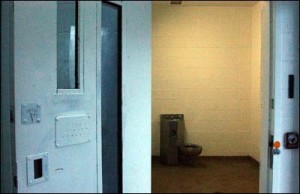

The six Youth Development Campuses run by the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) are intended to “provide secure care, supervision and treatment services to youth who have been committed to the custody of DJJ,” according to the DJJ website. All of the YDCs are also accredited schools that allow inmates to finish high school or earn their GED. However, that has not always been so.

Georgia also operates 20 Regional Youth Detention Centers where youth are held for shorter periods of time while they await their hearings in juvenile court. The RYDCs typically house 30 to 40 inmates.

Former correctional officer Victoria Floyd says, while she believes in rehabilitation, she worries DJJ’s new policies are too lenient on kids, leaving other inmates at risk.

“If one kid assaults another kid he may get a slap on the wrist,” she said, “but now the victim may be afraid to leave their room or go to education classes.” That means a guard must stay behind with the youth decreasing the amount of guards in the classes. That puts everyone, kids and guards, at risk, she says. Handing out tougher punishments will discourage further violence and reduce the chances of more serious incidents such as the one in Augusta earlier this week.

“I feel that for the future of Eastman YDC, in order to progress, things need to change as far as a stricter environment for the youth,” Floyd said.

And a large part of that involves hiring more correctional officers to reduce the ratio of guards to inmates, she says.

So why hasn’t the DJJ hired more guards?

Funds allocated specifically for YDCs in the DJJ budget have fluctuated over the last eight years, ranging anywhere from as high as $103 million in 2004 to as low as $61 million in 2011. (The 2012 budget allocates $70 million for YDCs.) It is not clear how much of that money is designated for staff and correctional officers in the YDCs or why Eastman is maintaining high ratios of guards to inmates.

According to one former administrator who worked at Eastman and asked to remain anonymous, DJJ has been fortunate that more inmates haven’t been hurt. He says the problem originates at the top of the DJJ, not in the YDCs themselves and that politics plays a large role in the decision-making.

No comments:

Post a Comment